|

From The Archives: Henry Hardinge

Friday, 28 November 2025

|

|

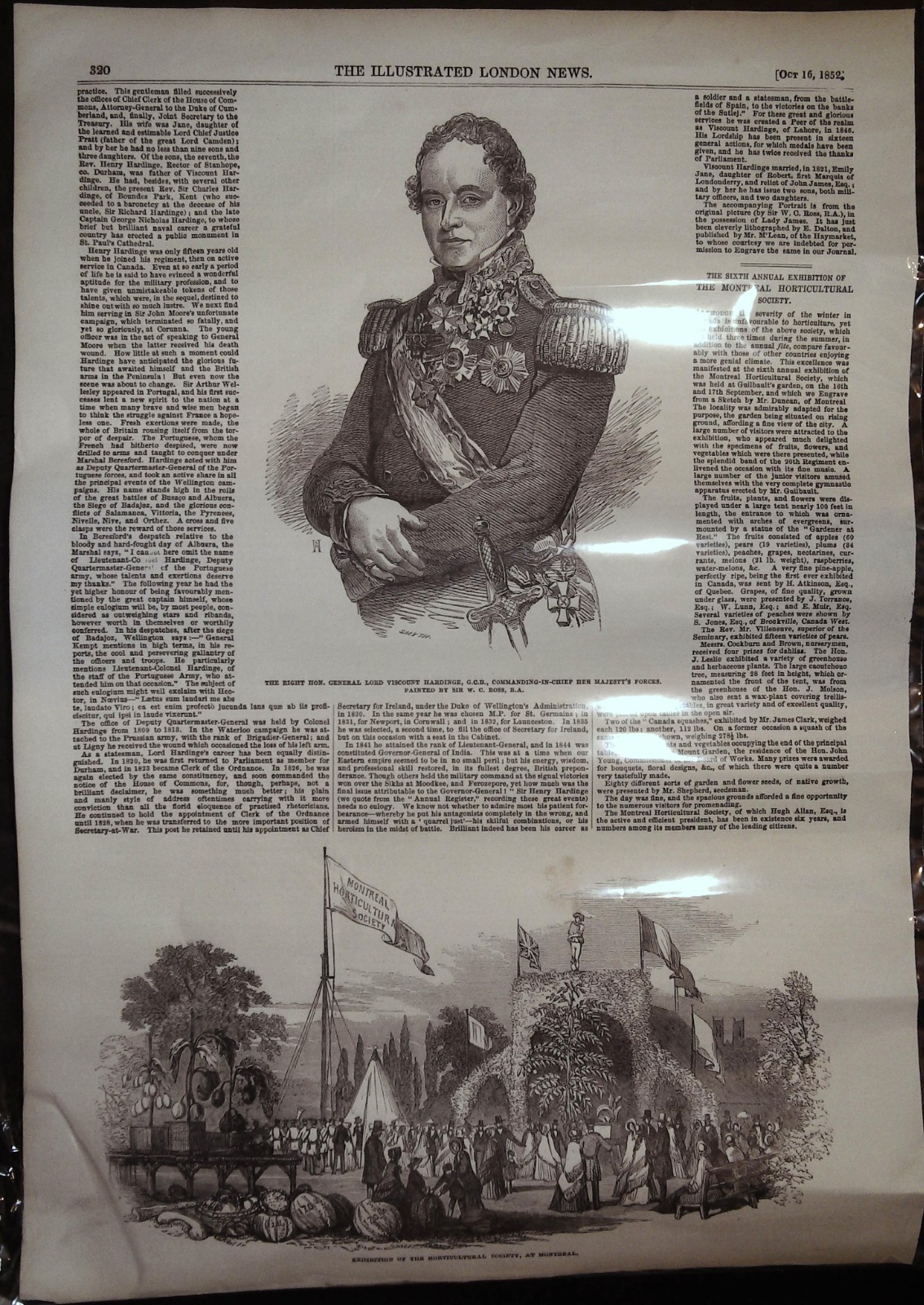

There is a dormitory in Poole House that, on the wooden board affixed above the door, proudly bears the name 'Hardinge 1797'. This refers to Henry Hardinge, one of the School's most significant alumni whose name appears in accounts of much of the early nineteenth century's colonial battles, from the Peninsular War and the Waterloo Campaign to the First Anglo-Sikh War and the Crimean War. Born in 1783, he was the son of his namesake the Reverend Henry Hardinge, the Rector of Stanhope. He spent much of his childhood in the Grove near Sevenoaks, under the charge of his two maiden aunts; both Henry and his younger brother Frederic attended Durham School, with Henry leaving in 1797 and Frederic entering in 1812. An account of his childhood days comes from his son Charles' biography, Viscount Hardinge (1891): "Before entering the army he was for some time at school at Durham; and he used to relate how he was always told off by his school-fellows for climbing the buttresses of the Cathedral and other services of danger in search of birds'-nests. When a boy, he was short in stature; and he would tell how his aunts made him hang with his arms on a door in order to stimulate his growth." One of the items in the archives is a page from an issue of The Illustrated London News, pictured above. Published on the 16th October 1852, the article picks up on his career after school. "Henry Hardinge was only fifteen years old when he joined his regiment, then on active service in Canada. Even at so early a period of life he is said to have evinced a wonderful aptitude for the military profession, and to have given unmistakable tokens of those talents, which were, in the sequel, destined to shine out with so much lustre." This last part obliquely refers to his experiences in the Battle of Corunna on the 16th January 1809, where he witnessed his commanding officer, Lieutenant-General Sir John Moore, killed in action. Hardinge was reporting the situation of the battlefield to him when a shot went through Moore's left shoulder. In a letter published later in 1809, Hardinge recalls attempting to remove Moore's sword to allow him to be more easily taken off the battlefield: "In the act of my unbuckling it, he said in his usual tone, 'It is as well as it is: I had rather it should go out of the field with me.' Observing the resolution and composure of his features, I caught at the hope that I might be mistaken in my fears of the wound being mortal, and remarked that I trusted when the surgeon dressed the wound he would be spared to us and recover. 'No, Hardinge,' he said, 'I feel that to be impossible.'" Hardinge was promoted to Major in April 1809, and then to Lieutenant Colonel in May 1811. That same month he was present at the Battle of Albuera, where his advice to General Galbraith Lowry Cole to immediately advance was credited with changing the course of the battle and winning the day. Hardinge would later gain a command, leading a Portuguese brigade in the storming of the heights of Palais in February 1814. He would receive the gold cross and five clasps for his efforts in Douro, Salamanca, Vittoria and others. This was not the greatest honour he received; to quote the above 1852 article, "…he had the yet higher honour of being favourably mentioned by the great captain [Arthur Wellesley, Duke of Wellington] himself, whose simple eulogium will be, by most people, considered as outweighing stars and ribands, however worth in themselves or worthily conferred. In his despatches, after the siege of Badajoz [in 1812], Wellington says: – 'General Kempt mentions in high terms, in his reports, the cool and persevering gallantry of the officers and troops. He particularly mentions Lieutenant-Colonel Hardinge, of the staff of the Portuguese Army, who attended him on that occasion.'" Wellington's letters to William Beresford would often call on requests of "Hardinge or some other staff-officer who has intelligence" to come to British Army headquarters to discuss military tactics. Upon Napoleon's return from Elba, Wellington instructed Hardinge to position himself near the French general to report on his movements. On the 16th June 1815, during the Battle of Quatre Bas, his left hand was shattered so severely that amputation at the wrist was determined necessary. Despite this, Hardinge would continue to command the Prussian contingent of the army until the withdrawal of allied troops from France in November 1818. Hardinge would then exchange his military sword for politics, being elected as a Tory MP in his boyhood Durham in 1820. An anonymous critic of Hardinge wrote to the 19th February 1820 issue of the Durham Chronicle during this election, writing under the name "Q in a Corner": "With respect to the 'Virgil' of the Hardinge family, 'not knowing, can't say.' Our sons at the Grammar School no doubt could tell us something of his 'latin verses'; but we never heard that Mr Carr [the School Headmaster in 1820] either gave them out as scanning tasks or pointed them out as fit studies to qualify the young rogues for acting the parts of free men at Elections." From July 1828 to July 1830, during the Wellington government, Hardinge was appointed as Secretary of War, a role he would return to in 1841 through to 1844. He would additionally serve as Chief Secretary for Ireland from July to November 1830 and then again during Robert Peel's government from 1834 to 1835. In 1844 he replaced his brother-in-law Lord Ellenborough as Governor-General of India, at the suggestion of Wellington. When the First Anglo-Sikh War (1845-1846) broke out, it was Hardinge who commanded some of the British forces. His appointment as Commander-in-Chief of the Forces in 1852 meant that he was responsible for the British Army during the Crimean War (1853-1856). It was this episode that was the black spot in Hardinge's career, as the Old Dunelmian, now approaching seventy, was criticised in the court of public opinion for the disasters that the lack of military preparation caused. In 1856, while presenting the report on the Crimean Inquiries Commission to Queen Victoria, he collapsed with a stroke, but still insisted on delivering the report. He would die later that year at the age of 72. Hardinge's remarkable career makes him rightly one of Durham School's most significant military alumni, and his life is a study in microcosm of the British Army throughout the Georgian and Victorian eras. Who would of thought that so much could have been achieved by the schoolboy climbing the Durham Cathedral roof, hunting for birds' nests?  |